![Roslyn’s Coal Miners Memorial Located in front of the “Old Company Store” [Updated: now known as the NWI Building]](http://roslyncemeteries.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/coal-miners-memorial-statue.jpg)

Located in front of the “Old Company Store”

By Paul Fridlund

May 10, 1892.

Benjamin Ostliff, an English immigrant, left home for the mine. For the father of six children this day promised something that had been infrequent lately. He would work a full shift in No.1 Mine in Roslyn. The family needed the money during this depressed time. For Ostliff, Roslyn had become home. After immigrating to the United States, he moved to Illinois. In 1886, he ventured west to Roslyn. He helped open the first mine under the direction of John Kangley and worked in the mines until 1888 before returning to Illinois. But disaster struck Roslyn that summer. Fire destroyed the town, and carpenters were needed. Ostliff returned to help rebuild the business section, and he remained. He was in Roslyn during the terrible strike of 1888, and he was a victim of the economic slowdown in 1892. In every respect, he was a pioneer miner in the development of the Roslyn coal fields. After filling the bottom of his lunch pail with water and placing sandwiches in the tray on top, Ostliff headed for the mine. There he joined 44 others. They represented the established miners of the area. Most were Anglo Saxon pioneers in the area but five were well-respected blacks. Only one of the group. Dominic Bianco was from southern Europe. Nearly all were family men, specially selected because the company felt they were more careful in the mines. For many miners, there was no work at all. The 45 men on the shift must have felt fortunate to have work. Dark clouds covered Upper Kittitas County on May 10, 1892. The day promised rain. It also brought disaster.

The Daily Record, Ellensburg, WA, Fri., August 18, 1989

Opening the Mines

In the early 1880s, prospectors roamed the hills looking for gold and other precious metals. Upper Kittitas County was still a virgin land, an unsettled wilderness in Washington Territory. In their explorations, miners reported finding traces of coal. Eventually, the Northern Pacific Railroad learned of this discovery, and in 1881 a railroad survey party visited the area. No coal was found. Two years later, the first settlers homesteaded in Upper County. One of the, C.P. Brosius, discovered coal on his ranch. Although he recognized the quality of the find, he paid little attention to it. His interest was in building a home in the wilderness. But others became involved. During 1883, four well-defined veins were discovered, and 13 claims were filed. The first large deposit was opened by George Virden and William Brannan in Ronald. The next year, Virden and Nez Jensen exported the first coal from the Roslyn area. In horse-drawn wagons they brought coal to Ellensburg, where it as sold to local blacksmiths. The following year coal prospectors found little success, but in 1885 the Roslyn vein along Smith Creek Canyon was discovered. The prospectors told Northern Pacific Railroad officials. Although the 1881 survey failed to locate coal, a second railroad survey crew discovered deposits from Masterson Gulch to Lake Cle Elum in May, 1886. Using diamond drills, they identified a number of promising sites. In August, 1886, the company opened its first mine. By the end of the year, the Northern Pacific Railroad reached Cle Elum, and the company began exporting coal. In building the transcontinental route, the Northern Pacific received every other section of land. The company had vast land holdings in Upper County, but the Northern Pacific wanted all the coal lands; so the company bought the claims of many settlers. When some settlers resisted, the railroad company contested the claims of 26 settlers in court, claiming the land was mineral and not agricultural. Two years later, the Secretary of the Interior ruled in favor of the settlers. Despite this setback, the Northern Pacific began the rapid development of the coal fields. 278 It also built the town of Roslyn. The town was platted a year later. The mines attracted miners from all over the country, and the area boomed as men sought work. The first shipment of 1,500 tons of coal left the Roslyn coal fields in December 1886. Of the miners who entered the No. 1 Mine on May 10, 1892, many were men who came when the mines opened. The included: Benjamin Ostliff, the father of six children, who helped open the first mine. Sydney Wright, father of four children, who came with his brothers James and Thomas and was among the first people to arrive in Roslyn. Joseph Cusworth Sr., an English immigrant and father of six children who arrived in 1887. Joseph Cusworth, Jr., the 21-year-old son of Joseph Sr., who helped support his five brothers and sisters. David Rees, Jr., a 19-year-old immigrant from Wales, and son of Thomas Rees. He arrived in 1887. Thomas Rees, the father of several children. Mitchell Ronald, the brother of mine superintendent Alexander Ronald and the father of four small children. There were other pioneer miners on the May 10, 1892, shift who helped open the mines.

Labor Trouble

Among the 45 miners who entered No. 1 Mine on that overcast afternoon of May 10 were six black men. They had come to Roslyn after a bitter labor strike in August 1888. The mines grew rapidly after opening in 1886. In the year ending Sept. 30, 1888, the output from the mines was 1,133,801 tons, an increase of 608,096 over the previous year. Miners worked 10 hours a day under adverse, dangerous conditions. The miners wanted the work day reduced from 10 to eight hours a day. Organized as the Knights of Labor, the workers also sought a closed shop. On Aug. 17, 1888, they went on strike. The company resisted their demands. Within a week, a crew of strike breakers arrived from Illinois. They were black. Striking miners were openly hostile to the new arrivals. As a precaution, the company sent 40 armed men to protect the black miners. The guards were called U.S. marshals, although they were actually bodyguards hired through a private detective agency. As they rode through Roslyn to Ronald, where the No. 3 Mine was opening , these guards flashed guns at Roslyn people watching the train pass. “These men exhibited weapons in threatening manners and are said to have passed through the said town…with guns at the windows of each of the said cars aimed at the large crowd of people standing in the vicinity of the depot.” A report to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior said. “There is a bitter feeling against the negroes and the United States marshals among the miners, and I fear there will be bloodshed over the matter,” the report said. The author described the armed men protecting the black strike breakers. “These men were regularly armed, uniformed, and officered in military style, and had thrown up fortifications of logs and earthworks, in front of which they had erected a barbed-wire fence to serve as an abattis,” he said. “The men were not under arms when I visited them, but it was not denied that they were supplied with magazines, rifles and side arms, and that regulations of the camp were substantially those of a military establishment. A number of negro laborers were quartered inside the camp.” Relations between the striking miners and the company, including the black strike breakers, remained tense. But in September, the striking miners went back to work without any concessions from the company. In fact, they accepted a 10-cents-a-ton reduction for piece work. White miners receive $1.15 a ton, while black miners were paid 85 cents a ton. But when the company announced it wouldn’t hire any of the strike leaders back, the miners struck again. Only the No.3 Mine in Ronald, operating with black strike breakers, remained open. For the next six months. Roslyn was a powder keg. On Christmas Day, the mule drivers who hauled coal from the mines went on strike. Again, the company responded by hiring strike breakers. More violence followed. A telegram to John Kangley, company president, in December, 1888, discussed the trouble that followed. “In taking the new (black) 279 drivers to Roslyn this afternoon, (company supervisors) Ronald and Williamson were surrounded and knocked senseless by strikers and disarmed afterward. Afterward (they were) run out of town. Several of the new men were badly used up. Mob rule reigns in Roslyn tonight,” the telegram said. The strike was eventually settled on the company’s terms. All the mines were operating by the end of February 1889. The first black strike breakers were considered “a corrupt lot”. The company filled their places with white workers and with other Blacks brought into the area. For two years, Blacks outnumbered Whites in the Roslyn area. But many were starved out in the years that followed, and only a few were employed in later years. Among the 45 miners who entered the No. 1 shaft on May 10, 1892 were six prominent Blacks. There were: Wesley Pollard of Virginia, who arrived in 1889. He was married. Rev. G. W. Williams, a miner since boyhood, who served as a minister in Roslyn. Press Lovin, a 31-year-old Virginia native, considered “virtuous, sober and highly respected by all”. Tobias Cooper, a “hardworking, saving and sober” husband and father who arrived in 1889. Scott Giles of Virginia, an experienced miner, who arrived in 1889. Elisha Jackson, a Roslyn resident for two years, who was considered “a general favorite among his people”. The strike of 1888 had been bitter, and feelings of prejudice remained. But when the afternoon shift entered No. 1 Mine on May 10, 1892, six Blacks were among the crew.

Economic Problems

While returning home from a dance in January 1892, George Forsythe slipped and severely sprained his knee. The superintendent of No.3 Mine in Ronald spent several days recovering from this painful injury, one that seemed to symbolize the frustrations of the new year. In March, Forsythe’s No.3 Mine was closed indefinitely. In 1890 the mine operated 260 days, sometimes with three shifts. A year later, the mine operated 160 days. And the demand for coal dropped even more in 1892. “The Roslyn and Ronald properties have been running at a loss for some weeks on account of the exceedingly dull coal market, and the prospects for an increase in the demand for several months yet are not very encouraging,” the Tacoma Tribune-News reported. “Our coal mines are not being worked at Roslyn because the cost is (priced) too high,” the Ellensburg Localizer said in April. “People here during the winter burned wood because of the high price of coal”. In Walla Walla, the newspaper said, people burned coal imported from Australia. “Roslyn should have the trade of Walla Walla and that also of the Union Pacific, but Roslyn has neither,” the localizer said. “Working in the slope was more remunerative than in the mine, the company having given men with large families the preference,” the Seattle Press-Times said. Those working on the shift had been given preference. “Work has been slack at the mines for some months past, men being employed only for one or two days in the week, so that their families have barely had means of subsistence,” the newspaper said. In this time of economic depression, all the miners needed to work. Thomas Brennan, father of nine children, had been ill for three months. May 10 was his second day of work during that period. It also explains why so many were prominent men, like No.3 supervisor George Forsythe and Mitchell Ronald, brother of the mines supervisor, Alexander Ronald.

Number One Mine

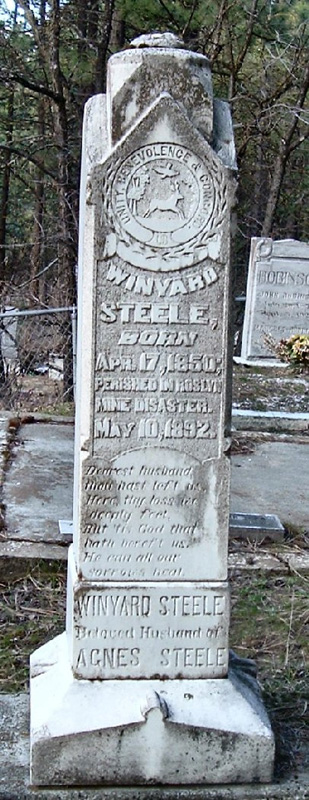

The No. 1 Mine was the first opened by the Northern Pacific, but the company was opening a new slope in 1892. The 8,000-foot slope had seven levels and was considered dangerous. Located in a narrow gorge with heavily wooded sides, the mine had a tramway that led from the mouth to railroad tracks about 500 yards away. “Reports have been circulated to the effect that the slope work has been considered unusually dangerous for the past three months,” the Press-Times said. “It is a significant fact that 280 a majority of the men who have been working in the slope are skilled miners. Many of the men had in their time been pit foremen or mine bosses. Every morning mines are inspected by competent foremen and his report is bulletined at the entrance of the mine. If there is danger, miners are forbidden to enter, and he goes ahead at his own risk.” In late March or early April, a gas explosion occurred in the slope, according to the Roslyn News. “The explosion which occurred about six weeks ago, in which a colored man by the name of Gregory was killed and several others badly burned, was a stern warning that possible precaution must be taken to prevent future clamation,” the newspaper said. During this explosion, 21-year-old Joe Cusworth saved a fellow miner. “He entered a death pit in the mine here about six weeks ago at the risk of his life and brought out one of his fellow workmen who would have perished had it not been for the brave and noble action of Joe,” the News said. All the men knew the dangers of mining, like Winyard Steele. “Many were the injuries he sustained, having his arms, legs, ribs and other parts of the body badly bruised and jammed at various times,” the News said. On the morning of May 10, 1892, gas was reported in the mine. The following notice was posted at the entrance: “Mine No. 1 – Fire damp in fourth, west airway; fifth, east section and airway. J. Shaw.” All these gases were removed by fireman John Shaw and the men put to work,: the Press-Times said. The shift went to work at 7 p.m. The mine was reported clear of gas when the men entered the mine. There was nothing particularly unusual, and the miners probably had no cause for alarm. For them, it was good to be working.

Explosion

Inside the mine, many of the miners sat eating lunch at 12:45 p.m. Others continued working. They used naked lamps to see. These lamps had exposed flames that reflected from their helmets. Outside the entrance, a heavy rain began pouring down. A mule driver was just leaving the mine with a small train of cars. Boom, BOOM! The man and mules were knocked to the ground. The cars tipped and fell as the earth shook. “There were fourteen cars on the track at the mouth of the tunnel,” the Ellensburg Localizer said. “Some of the cars were demolished and others driven with great force down the track.” “The report was heard all over town and for more than a mile away in the surrounding country,” the Press-Times said. “No one needed to inquire what had happened. The report told its own tale of sorrow to every resident of the village… The explosion, the shock, and the cloud of smoke, and the cloud of smoke and gas which followed it was notice to every person in Roslyn that death had come very clear to him – more than likely into his own household.” Inside the mine gas exploded, causing the first boom. The concussion ran down the shaft, hit the end and bounced back, like the explosion in the barrel of a gun. “Heavy iron water pipes were bent and twisted like wire, solid fir timbers 12×14 were broken into tinder, huge boulders and chunks of coal were picked up and hurled many feet up the passage,” the Roslyn News said. “Persons standing near the entrance were blown about like leaves,” “Several of the bodies (miners) were burned and mangled in such a manner that all semblance to human beings was effaced,” the News said. “The majority were easily recognized. From the different positions in which the miners were found, many persons were led to the conclusion that some lived for a time after the explosion had taken place. Several had their shirts over their heads, as if to keep from inhaling the poisonous air. Others had their hands over their faces. In the case of John Foster, Winyard Steele, Michael Hale and Mitchell Ronald, who were supposed by many to have lived for some time after the shock…these four miners were working together.”

The Tragedy

Outside, everyone in town rushed to the mine and “it was soon surrounded by an eager and sorrowing crowd, which increased rapidly until everybody who could go was there,” the Press- Times said. “A hard rain was pouring at the time, but nobody heeded it. There was too much anxiety to know the extent of the disaster, how it had happened and what, if anything, could be done to rescue the men in the mine.” “The shaft was full of smoke and debris,” the newspaper continued. “It even seemed to be on fire. The horrors of a general and shocking bereavement seemed about to be increased by the cremation of the dead almost within sight of their sorrowing friends.” Women who had husbands working in the mines were frantically rushing about the mouth of the tunnel eager to learn the fate of those dear to them,” the Ellensburg Localizer said. “The scene presented was appalling in the extreme.” “Poor women and children whose lot in life at best is a hard one, now thronged about the mine and begged piteously for somebody to save their husbands, fathers, sons or brothers,” the Press- Times said. “The lamentations of the Negroes were particularly pitiful. Some seemed to be dazed by their loss, and the very silence of their woe appealed to every observer. Others begged to be told what it was then impossible to know, and some were with difficulty restrained from rushing into the tunnel in the hopelessness of their desire to do more than could be done.” Thomas Weatherly, son of Jacob Weatherly, had to be physically restrained from rushing into the shaft to search for his father. Stunned, dazed and weeping, people stood outside the dust-choked mine as the rain continued to fall. A rescue party was organized, but for the time being, nothing could be done. Whatever the fate of the miners, people on the outside were helpless in the face of tragedy.

The Rescue Party

When asked to form a rescue party, many miners volunteered to search for their companions. As the dust settled, the first party went into the mine. “Gang after gang goes down in the face of the warning of gangs forced to come up by the overpowering gas, determined to leave no effort untried that may lead to the rescue of their mates,” the Press-Times said in an extra edition. “Coal black negroes and white men forget race and work together in harmony for the recovery of the victims, hoping against hope to rescue alive some more fortunate one whom death may have spared.” “The outpour of deadly gas from the tunnel was too great to permit the search being prosecuted for any length of time,” the Ellensburg Localizer said. “Every ten minutes relief gangs were sent in and the work was kept up this way until the foreman, George Harrison, counseled that it was too risky to continue the search, as to remain would be to suffocate from the deadly fumes. At 12 o’clock on the night of the 10th the rescue was abandoned.” Fourteen bodies had been recovered. “The last three victims found in the fifth level east of the slope were laying on their faces, facing towards the main slope, and were not maimed,” the newspaper said. “One evidently struggled against death, but the fire damp asphyxiated him.” “Work during the night was pushed far enough to satisfy even the most sanguine that no chance remains of recovery of any alive,” the Localizer said. “The day broke in a drizzling rain, which continued at intervals all yesterday. The sun shone now and then to drive away the gloom, but it invariably turned behind the great dark clouds and permitted it to grow denser,” the Press-Times said. “Daylight was hailed with relief by the men who were at Mine No. 1 working like heroes to render succor to their imprisoned comrades. Spurred by the hope – through the spark of hope was burning only very faintly – that life might still be in the bodies of some of the entombed men, the rescuing parties worked with the energy of desperation… Firedamp almost strangled them occasionally, and they would be forced to seek fresh air above the ground. Back again they would go and work as they had worked before. The suffocating gas drove them back once, twice, a dozen times, but they could not be kept back. Among the men forming the rescue party was Ed Dunstan, a miner who was severely injured 282 in the explosion six weeks earlier. Another was Thomas Weatherly, the young man restrained the first day. Carrying a lantern, he approached the mine to search for his father. At first he was told he couldn’t enter the mine, but after pleading his case, he was allowed to join one of the rescue parties. It took two more days to recover all the dead.

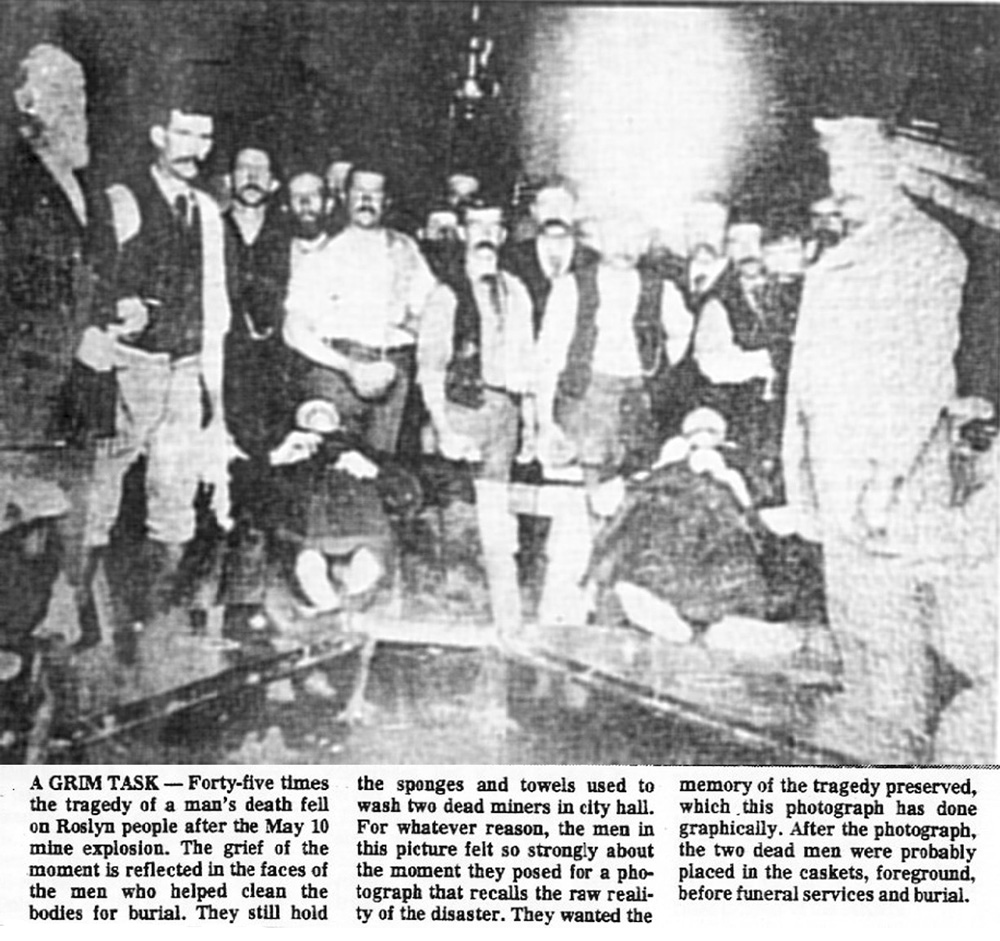

The Morgue

“The bodies were taken in improvised wagons to the town hall, where they were deposited on long tables side by side, that they might be viewed and identified,” the Localizer said. “The distressing scenes of the afternoon were reenacted at the town hall, the women coming thither to claim their dead and mourn for them. The bodies were divested of their clothing and laid in rows of two each and their faces washed of blood and the black encrusted on them. Then was revealed the horrible extent of the injuries inflicted.” “Men’s heads were blown away, their arms severed, their eyes blown out and their skin blackened, scarred and bruised,” the Localizer continued. “Three of them were apparently uninjured. These three had been found lying in the fifth level, east of the main slope, flat upon their faces, where they had thrown themselves to escape the baleful effects of the afterdamp, only to be asphyxiated by it.” “Most of the bodies are horribly burned and mutilated,” the Press-Times said. “The dead are being taken care of as fast as brought out.” A Tacoma undertaker arrived in Roslyn, bringing with him 40 caskets and some attendants. “As the shades of (Wednesday) night began to fall, friends of the dead men whose bodies had been recovered could be seen in different parts of the town carrying coffins in which was all that was mortal of their friends,” the Press- Times said. The first 12 victims were buried on Thursday, May 12. After a service in Unity Hall, the procession moved down Pennsylvania Avenue to the cemetery. “The funeral procession was a large one,” the Press-Times said. “The Knights of Pythias, I.O.O.F, S.O.G.T, and the Masons, dressed in full regalia, were in attendance.” Even as the procession moved towards the cemetery, the work of excavating graves continued. “The sounds of (dynamite) blasts fill the air, which are being fired to expedite the work of digging the numerous graves,” the newspaper said. Burials began before the last bodies were recovered. It took three days to recover the remains of the last victims.

Grief

“The gloom of death hangs heavily over this town today and has spread its dreaded presence into almost every one of the hundreds of little homes,” the Press-Times said. “Scarcely a man or woman, boy or girls can be seen who has not lost relative – either a father, husband or friend. In keeping with the oppressive feeling of death which hovers over the town or the unnatural stillness. The people walk up and down the streets leading to the scene of Tuesday’s terrible disaster almost stealthily and converse whispers. Little knots of men congregate at street corners and talk almost in whispers, of the horrible fate of their relatives and friends. Not one face in the hundreds seen outside of the residences, which are in themselves alone suggestive pictures of poverty, is free from traces of bitter tears. Eyes red with weeping and faces drawn with anguish tell in mute language of the bitter and sorrowful night passed by the 2,000 souls here.” The newspaper cited many instances of grief brought by the tragedy, such as the case of Josephs Cusworth’s wife who also lost a son in the mine. “When Mrs. Cusworth heard of the disaster, she ran like a mad woman from her home of poverty to the mine,” the newspaper said. “Her face became drawn with the mental torture which she passed through. Her ravings at the mine were extremely pitiful. For probably half an hour tears streamed from her eyes, and no one could comfort her. Suddenly, as if seized with an inspiration, she exclaimed: ‘ My husband is not dead. My boy will come home with him to supper.’ She turned and retraced her 283 steps to her home and set about making preparations for supper. She set the table with unusual neatness, and made every arrangement for the meal in the tidy manner of a good housewife. Her children were called into the house and washed and their pallid little faces made to look bright and cheerful. Six o’clock came but her loved ones did not come. Seven o’clock and still husband and son failed to arrive. Her neighbors watched her with feelings of profound pity. Before 8 o’clock the poor woman, the poor woman, still nourishing her delusion, went outside and spoke to a man who had just left the mine. ‘Is it true?’ she asked in a whisper. ‘My God, Mrs. Cusworth, it is only too true,’ came the answer from the stout-hearted fellow, with tears in his eyes. “Not a sound escaped the woman’s lips,” the newspaper continued. “She returned to her home and there she wept. Later in the evening her grief became terrible. All night long she walked about her little frame house crying in a most heartrending manner. Today she is weak from exhaustion.” The newspaper cited other personal tragedies. Thomas Rees and his son, David, were killed while working side by side. They supported a large family with children ranging in age from a few months to 12 years old. Winyard Steele’s wife also lost her brother, Mitchell Hale. William Hague left an invalid mother and a crippled sister. His mother told the Press-Times reporter about the last day in Hague’s life. “William overslept himself on Tuesday morning. I was feeling better than usual and called him to get up and go to work,” she said. “Oh, I don’t feel like working today,” he replied. “Now, William, get up, I said to him, and he obeyed. I wish he never left home,” the heartbroken mother said as tears filler her eyes. In the small company telegraph office, women sent word to relatives about their dead or missing husbands. “What do you want to say?” an operator asked one woman whose husband was still missing. “Just the same as the others. Tell father John is with the rest of them,” the woman said with tears in her eyes. “I went about among the cabins of the poor today,” the Press-Times reporter said. “The woman, with eyes red from weeping, answered the knock and were unable to talk without bursting into tears. In nearly every instance they are destitute.

“The gloom of death hangs heavily over this town today and has spread its dreaded presence into almost every one of the hundreds of little homes,” the Press-Times said. “Scarcely a man or woman, boy or girls can be seen who has not lost relative – either a father, husband or friend. In keeping with the oppressive feeling of death which hovers over the town or the unnatural stillness. The people walk up and down the streets leading to the scene of Tuesday’s terrible disaster almost stealthily and converse whispers. Little knots of men congregate at street corners and talk almost in whispers, of the horrible fate of their relatives and friends. Not one face in the hundreds seen outside of the residences, which are in themselves alone suggestive pictures of poverty, is free from traces of bitter tears. Eyes red with weeping and faces drawn with anguish tell in mute language of the bitter and sorrowful night passed by the 2,000 souls here.” The newspaper cited many instances of grief brought by the tragedy, such as the case of Josephs Cusworth’s wife who also lost a son in the mine. “When Mrs. Cusworth heard of the disaster, she ran like a mad woman from her home of poverty to the mine,” the newspaper said. “Her face became drawn with the mental torture which she passed through. Her ravings at the mine were extremely pitiful. For probably half an hour tears streamed from her eyes, and no one could comfort her. Suddenly, as if seized with an inspiration, she exclaimed: ‘ My husband is not dead. My boy will come home with him to supper.’ She turned and retraced her 283 steps to her home and set about making preparations for supper. She set the table with unusual neatness, and made every arrangement for the meal in the tidy manner of a good housewife. Her children were called into the house and washed and their pallid little faces made to look bright and cheerful. Six o’clock came but her loved ones did not come. Seven o’clock and still husband and son failed to arrive. Her neighbors watched her with feelings of profound pity. Before 8 o’clock the poor woman, the poor woman, still nourishing her delusion, went outside and spoke to a man who had just left the mine. ‘Is it true?’ she asked in a whisper. ‘My God, Mrs. Cusworth, it is only too true,’ came the answer from the stout-hearted fellow, with tears in his eyes. “Not a sound escaped the woman’s lips,” the newspaper continued. “She returned to her home and there she wept. Later in the evening her grief became terrible. All night long she walked about her little frame house crying in a most heartrending manner. Today she is weak from exhaustion.” The newspaper cited other personal tragedies. Thomas Rees and his son, David, were killed while working side by side. They supported a large family with children ranging in age from a few months to 12 years old. Winyard Steele’s wife also lost her brother, Mitchell Hale. William Hague left an invalid mother and a crippled sister. His mother told the Press-Times reporter about the last day in Hague’s life. “William overslept himself on Tuesday morning. I was feeling better than usual and called him to get up and go to work,” she said. “Oh, I don’t feel like working today,” he replied. “Now, William, get up, I said to him, and he obeyed. I wish he never left home,” the heartbroken mother said as tears filler her eyes. In the small company telegraph office, women sent word to relatives about their dead or missing husbands. “What do you want to say?” an operator asked one woman whose husband was still missing. “Just the same as the others. Tell father John is with the rest of them,” the woman said with tears in her eyes. “I went about among the cabins of the poor today,” the Press-Times reporter said. “The woman, with eyes red from weeping, answered the knock and were unable to talk without bursting into tears. In nearly every instance they are destitute.

Relief

“The grief of many is pitiful to behold,” the Press-Times said. “Wives left with large families to care for, children who for years have been without the protecting influence of a mother find themselves now also without the care of a father; weak and aged widows who have been dependent upon the support of sons, and girls who have had no protector or provider except an honest, industrious and hardworking brother, now see starvation staring them in the face.” Relief efforts started immediately. The company distributed $500 worth of groceries the first day. Roslyn Mayor Charles Miller organized a committee to care for the families of dead miners. “We must help those poor women and children and must do so at once,” he said. “The men had been working an average not more than two days a week, and very few had a single cent saved.” Throughout the state, towns formed committees that raised disaster relief money. Seattle alone contributed $1,776. Within a few days, $7,000 poured in from outside towns and another $2,000 was raised in Roslyn. But it wasn’t enough. A coroner’s inquest was conducted. “We find that the deceased persons (naming the miners) came to their death by the explosion of fire damp in Mine No. 1,” the inquest determined. “We further find that the said explosion was caused, in our opinion, by deficient ventilation.” The Northern Pacific Coal Company paid relatives of dead miners a cash settlement.

Aftermath

Many of the widows left Roslyn, while others stayed. For them, the years that followed were hard. Perhaps typical was the story of Mrs. Thomas Brennan, as told by her daughter, Jinnie Oversby, in 1955. When her husband was killed, Mrs. Brennan was left with seven children. She continued living in Ronald. “I can see mother today as she knelt in the little Catholic Church on the hill, attending her husband’s funeral service, far from her old home and relatives; now there were seven children to care for,” Mrs. Oversby wrote. “She was not alone in her sorrow, as six other widows were attending the same service. “Roslyn was a mission field at that time, and a Priest came from Ellensburg several times a year,” she said. “While Father Kuster was conducting the funeral services for the deceased miners, five young couples were waiting in the church to be married, at the same time a number of young mothers were seated in the rear of the church holding their infants and praying that Father would have time to baptize them. It seemed that a cross section of life was enacted there that day.” “Then the struggle for existence began in earnest,” she continued. “To help support her family, Mother often carried a bundle of laundry from Roslyn to Ronald and back again, hoping to earn a mere pittance. In one case the milliner for whom she worked refused to pay her and insisted upon her taking an outmoded hat instead. Much to mother’s dismay, she walked back the four miles to No. 3 with an old hat but no money.” In 1897, Thomas Brennan’s widow married Luke McDermott and the family moved to Prosser. After the mine disaster of May 10, 1892, life went on. For the families of dead miners, survival was a struggle. Eventually, the pain eased, but the tragedy was never forgotten. It remains the worst tragedy in the history of Kittitas County.

45 Miners Died

- Joseph Bennett

- Dominic Bianco

- John Bowen

- George Brooks

- Joseph Browitt

- Harry Campbell

- G. Cooper

- Joseph Cusworth Sr.

- Joseph Cusworth Jr.

- Phillip D. Davis

- Herman Daister

- Andrew Erlandson

- George Forsyth

- Richard Forsyth

- John Foster

- Scott Giles

- Robert Graham

- Mitchell Hale

- Frank Hannah

- James Hewitson

- William Hague

- John Hodgson

- Thomas Holmes

- James Housbon

- Elisha Jackson

- John D. Lewis

- John Mattie

- Dan McClellan

- James Morgan

- George Moses

- Benjamin Ostliff

- Charles Palmer

- William Penall

- Leslie Pollard

- David Rees

- Thomas Rees

- William Robinson

- Mitchell Ronald

- Preston Saing

- J. D. Senis

- Robert Spotts

- Winyard Steele

- Jacob Weatherly

- G. W. Williams

- Sydney Wright

Obituaries

These obituaries were but two from The Cle Elum Echo of those who died in the Number 1 mine explosion in Roslyn, Washington State, on May 10, 1892.

located in the Old Knights of

Pythias Cemetery, Roslyn, WA

Picture taken on March 9, 2005 [KSW]

“JAMES MORGAN was a Welshman, born in the beautiful little watering town of Abbrys, on the shores of Cardigan Bay in Wales. Seventeen years ago he came to the United States settling in Pennsylvania, and following there for some time his vocation as a coal miner. Since then he has plied his calling in the states of Maryland, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Indian Territory, coming to this state about three years ago and locating in Roslyn. He is not known to have any relatives in this country, but has a brother in the town of Mountain , South Wales, Great Britain. Courtly and modest in his address and sincere at all times, we found in Jimmy Morgan, beneath the habiliment of a coal miner, a man of sterling worth and a gentleman. He was a member of the order of Knights of Pythias and belonged to the local lodge of that order in Murphysboro, Illinois.”

See Also:

New book pays tribute to 45 Roslyn Miners killed in 1892 explosion

http://roslyncemeteries.org/mine-4-october-3-1909-10-miners-died/

RELATED EXTERNAL LINKS:

- Ewanida Rail Records – Roslyn Cemeteries, Kittitas County, Washington

- HistoryLink.org – Worst coalmine disaster in Washington history kills 45 miners at Roslyn on May 10, 1892.

- Ellensburg Daily Record – Roslyn Remembers 1892 Mine Collapse

- GenDisasters.com – Roslyn, WA Mine Explosion, May 1892

- Washington Rural Heritage – 1892 mine disaster: bereaved widows